Whereas bombing raids in the early and mid part of the 20th century involved hardly any direction, any bombing that we do today is going to be highly precise. This so-called smart bombing has constituted one of the great military advances over the past several decades. It’s efficient, cost-effective, and saves civilian lives. Now keep that in mind as I move into the non-military world of fighting cancer.

In one form or another researchers have been working to create DNA carrying/laden devices for years now. The application potential is huge, but the area that has received some of the greatest focus has been cancer research. The drugs and treatments we have now are inexact and not always effective. Aside from often killing healthy cells, thus leading to weight and hair loss, general illness, and other negative side-effects, they don’t always kill every cancer cell. Even surgery can be a bad thing at times. Consider for a moment what tumors need. More than perhaps anything is a blood supply. (The same goes for your regular cells; your skin cells are too far from a blood source, hence why they are little more than dead keratin.) In order to get their supply of blood, tumors must induce angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels. They do this by releasing certain stimulators. They also release inhibitors, but not enough to overwhelm the stimulators. However, these inhibitors have no problem traveling through the blood stream. The result is often the suppression of secondary tumors, especially if they are nearby. So when a surgeon removes a primary tumor, those other, previously restricted secondary tumors will have a chance to grow. And that is no good, of course. In short, the more exact we can get in destroying cancerous cells, the better off we will be.

Enter DNA nanobots.

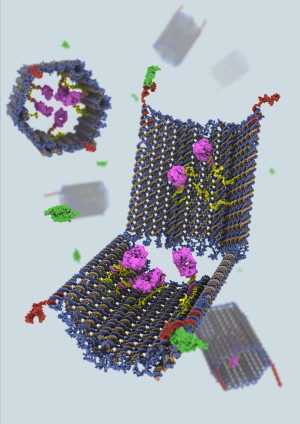

I like to think of these as smart bombs of cancer cells. They are bits and pieces of DNA naturally self-assembled into a particular shape (the barrel in the background) that is prepared to deliver a payload. That payload (the purple/pink stuff) is attached to specific strands (the yellow/green stuff) inside the DNA barrel structure. This is all held together by strands of DNA which are programmed to recognize specific molecules on the target cells (in this case, cancer cells). When the DNA attaches to these molecules, it changes shape and opens up the barrel. The payload is then free to enter into the target cell, inducing apoptosis (cellular suicide). Experiments have shown that these DNA robots are able to avoid healthy cells during this process.

There are, of course, limitations to this technology. Take malaria, for instance. It would be difficult to target most strains (such as P. vivax and P. falciparum) because they get inside hemoglobin rather than attach to the outside of anything. That makes them effectively invisible to both our immune system and these nanobots. Strategies for fighting that disease will tend towards the sort of medications we’re using now combined with bed nets and efforts to destroy mosquito habitats.

Still, this is exciting. I say that about most cancer-related advances, but I don’t feel I’m ever overdoing it. Every little bit of progress is crucial, even the bits that don’t pan out. I have hopes for this one, though. Even if it doesn’t end up being pragmatic in application, it still has the potential to 1) increase our understanding of cancer and 2) be used in so many other ways. Three cheers for science.

Filed under: Biology | Tagged: A Logic-Gated Nanorobot for Targeted Transport of Molecular Payloads, Angiogenesis, cancer, DNA nanobots, DNA origami, George M. Church, Ido Bachelet, Journal, Nature, Science, Shawn Douglas | 2 Comments »