I am again following a specific chapter in Jerry Coyne’s Why Evolution is True.

Natural selection molds what it is given. It does not create new features (mutations, however, can create new traits, which can then be molds, ignored, or actively destroyed by natural selection). If this claim is true, then we should expect to see remnants. Natural selection is not a magic wand. It will not cleanly dispose of its waste every time, or even most of the time. This is why we have vestiges.

A vestigial trait is a feature of a species which no longer performs the function for which it evolved. The first one of which everyone thinks for humans is the appendix. It is probably useless. Some arguments have been mounted which say that it may contain bacteria that is useful for the immune system, but I generally find the argument weak. But even if it is true, the appendix is still vestigial because it did not evolve for the purpose of assisting in infection-fighting.

In some of our cousins, near and far, the appendix is much larger than ours. In these instances, the animals are always plant-eaters like rabbits or kangaroos. In our closer cousins like the lemur, they also have a larger appendix, and of course they are mostly plant-eaters. However, when we move to other primates like oranguatans, the appendix becomes smaller. This is because they have less leafy diets. The appendix for these animals serves its original function: it breaks down cellulose into usable sugars with the bacter it contains. (This is why I find the bacteria-for-the-immune-system argument to be weak – appendix bacteria serves a different function in our cousins.)

It should now be clear that the appendix is a vestigial organ in humans. It no longer serves its original purpose, but most of us maintain it. One good reason may be related to appendicitis. This is when the appendix is too narrow and becomes clogged. Back in the day, 20% of people who got this died (and 1 out of every 15 people got it – that’s 1 out of every 100 people dying of this; that’s some very strong natural selection, indeed). Now, we have surgery to fix this, so of the 1 out of 15 who get this condition, only 1% will die. That’s a good reason why it’s being maintained now, but for millions of years, humanity had no surgeons. That left a small, narrow organ ready to kill a large swath of people. It may have been maintained because when it become too small, it caused death too easily. All those people already dying from this didn’t need more people to join them. The risk of death from its evolutionary eradication may have been too much. People with an extra small appendix contributed less to the gene pool than those with slightly larger appendixes.

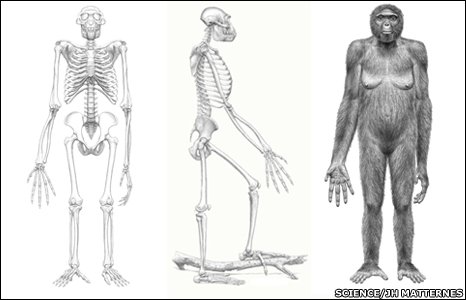

Again, it is important to remember that vestigial does not mean functionless. It refers to a trait which is still present in a species but does not serve its original function. Whales still carry with them vestigial pelvises and leg bones. These vestiges serve some purpose: they help to anchor some muscles. This only makes sense in the light of evolution. An instance of special creation holds no water because bones specifically made in the shape of pelvis and leg bones aren’t necessary. They’re inefficient. Within the light of evolution, however, this all fits together. Whales are descended from terrestrial animals (the indonyus I mentioned in my last post). When they took to water more and more over millions of years, they gradually lost their need for these bones. They were co-opted as muscle anchors in some instances, but they are not all absolutely necessary to the well-being of a whale. So while this vestigial feature has some use, it is still vestigial because whales are not using it to walk around anymore.

I have emphasized species a couple times in this post. This is because I want to make clear the difference between an atavism and a vestigial trait. A vestigial trait, as we have seen, is something which is the norm for all the members of a species. An atavism, however, is not. It shows up in individuals and is an anomaly.

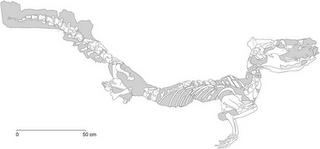

It is important to note that atavisms are not just random mutations, simple monstrosities. They are the appearance of ancestral traits, reawakened in an extant individual. A person born with six toes is not an example of an atavism because none of our ancestors had six toes. A whale, however, born with a leg is an example. While its pelvic bone is an old trait common among all members of the species, a leg is an anomaly.

The best explanation for atavisms is that they are the re-expression of old genes. They are not perfect expressions because the genes have deteriorated or accumulated mutations while remaining unused in the genome They are crude reenactments of ancestral species long extinct.

In 1980, E.J. Kollar and C. Fisher of UConn produced an atavism in the laboratory. They combined tissue from the lining of the mouth of a chicken embryo on top of tissue from the jaw of a developing mouse. The underlying mouse tissue could not produce teeth on its own, but with the chicken tissue, it did. Of course, chicken do not have teeth. Kollar and Fisher inferred that molecules from the mouse tissue reawakened something in the chicken tissue. In other words, chickens had the genes for making teeth, but didn’t quite have everything needed. Many years later, scientists showed that birds do indeed have a genetic pathway for producing teeth. They are just missing one protein. That protein, unsurprisingly, is present in mice.

This shouldn’t be a new paragraph, but I don’t want anyone to skim over or miss the big point. An animal cannot just have a genetic pathway for producing teeth by chance. It is far, far too complicated. We aren’t talking about a couple amino acids in the correct sequence: this is about groups of genes interacting in specific ways to produce a specific feature. Birds have this pathway, sans one protein. This is because they evolved from toothed reptiles. These reptiles, what with those teeth and all, had a genetic pathway to producing teeth. Over time, birds had no need for teeth, but still had the remnants of their reptilian ancestry. This makes no sense in the framework of instant creation. There exists this complicated pathway that could not exist simply by chance. Yet there it is. The pathway itself is vestigial (present in all members of the species), but its activation is an atavism (occurs in anomalous individuals). Only in the light of evolution is any of this explained.

In some of our cousins, near and far, the appendix is much larger than ours. In these instances, the animals are always plant-eaters like rabbits or kangaroos. In our closer cousins like the lemur, they also have a larger appendix, and of course they are mostly plant-eaters. However, when we move to other primates like oranguatans, the appendix becomes smaller. This is because they have less leafy diets. The appendix for these animals serves its original function: it breaks down cellulose into usable sugars with the bacter it contains. (This is why I find the bacteria-for-the-immune-system argument to be weak – appendix bacteria serves a different function in our cousins.)

It should now be clear that the appendix is a vestigial organ in humans. It no longer serves its original purpose, but most of us maintain it. One good reason may be related to appendicitis. This is when the appendix is too narrow and becomes clogged. Back in the day, 20% of people who got this died (and 1 out of every 15 people got it – that’s 1 out of every 100 people dying of this; that’s some very strong natural selection, indeed). Now, we have surgery to fix this, so of the 1 out of 15 who get this condition, only 1% will die. That’s a good reason why it’s being maintained now, but for millions of years, humanity had no surgeons. That left a small, narrow organ ready to kill a large swath of people. It may have been maintained because when it become too small, it caused death too easily. All those people already dying from this didn’t need more people to join them. The risk of death from its evolutionary eradication may have been too much. People with an extra small appendix contributed less to the gene pool than those with slightly larger appendixes.

Again, it is important to remember that vestigial does not mean functionless. It refers to a trait which is still present in a species but does not serve its original function. Whales still carry with them vestigial pelvises and leg bones. These vestiges serve some purpose: they help to anchor some muscles. This only makes sense in the light of evolution. An instance of special creation holds no water because bones specifically made in the shape of pelvis and leg bones aren’t necessary. They’re inefficient. Within the light of evolution, however, this all fits together. Whales are descended from terrestrial animals (the indonyus I mentioned in my last post). When they took to water more and more over millions of years, they gradually lost their need for these bones. They were co-opted as muscle anchors in some instances, but they are not all absolutely necessary to the well-being of a whale. So while this vestigial feature has some use, it is still vestigial because whales are not using it to walk around anymore.

I have emphasized species a couple times in this post. This is because I want to make clear the difference between an atavism and a vestigial trait. A vestigial trait, as we have seen, is something which is the norm for all the members of a species. An atavism, however, is not. It shows up in individuals and is an anomaly.

It is important to note that atavisms are not just random mutations, simple monstrosities. They are the appearance of ancestral traits, reawakened in an extant individual. A person born with six toes is not an example of an atavism because none of our ancestors had six toes. A whale, however, born with a leg is an example. While its pelvic bone is an old trait common among all members of the species, a leg is an anomaly.

The best explanation for atavisms is that they are the reexpression of old genes. They are not perfect expressions because the genes have deteriorated or accumulated mutations while remaining unused in the genome They are crude reenactments of ancestral species long extinct.

In 1980, E.J. Kollar and C. Fisher of UConn produced an atavism in the laboratory. They combined tissue from the lining of the mouth of a chicken embryo on top of tissue from the jaw of a developing mouse. The underlying mouse tissue could not produce teeth on its own, but with the chicken tissue, it did. Of course, chicken do not have teeth. Kollar and Fisher inferred that molecules from the mouse tissue reawakened something in the chicken tissue. In other words, chickens had the genes for making teeth, but didn’t quite have everything needed. Many years later, scientists showed that birds do indeed have a genetic pathway for producing teeth. They are just missing one protein. That protein, unsurprisingly, is present in mice.

This shouldn’t be a new paragraph, but I don’t want anyone to skim over or miss the big point. An animal cannot just have a genetic pathway for producing teeth by chance. It is far, far too complicated. We aren’t talking about a couple amino acids in the correct sequence: this is about groups of genes interacting in specific ways to produce a specific feature. Birds have this pathway, sans one protein. This is because they evolved from toothed reptiles. These reptiles, what with those teeth and all, had a genetic pathway to producing teeth. Over time, birds had no need for teeth, but still had the remnants of their reptilian ancestry. This makes no sense in the framework of instant creation. There exists this complicated pathway that could not exist simply be chance. Yet there it is. It serves for function. The pathway itself is vestigial (present in all members of the species), but its activation is an atavism (occurs in anomalous individuals). Only in the light of evolution is any of this explained.

Finally, this brings us to dead genes: more accurately, pseudogenes. These are genes which are merely remnants – genes which serve no function because they are no longer intact or expressed properly (as proteins). If evolution is true, then it predicts that many species should have these dead genes, and other species should also have some these genes, but in normal form. An act of special creation makes the opposite prediction – (well, sort of a prediction) – no dead genes should exist because no species have any evolutionary histories.

As it turns out, there are plenty of pseudogenes. All species carry them, but humans specifically carry about 2,000 (we have 25,000 – 30,000 total genes). One such gene is GLO. It produces an enzyme used to make Vitamin C from simple sugar glucose. As evolution predicts, other species have this gene, but it is not in primates (among a few others). Primates have a pseudogene of GLO. They maintain the genetic pathway needed to get to the point where the GLO gene should be activated, but it never follows through. That is, there are four steps in making Vitamin C. GLO is the fourth step. Primates have the first three, but not GLO. This is because the gene has a single nucleotide missing. It is the very same nucleotide which is missing in other primates. As I’ve discussed in the past, shared errors are very good evidence for common descent.

Only in the light of evolution does GLO make sense. All mammals inherited this gene at one point about 40 million years ago. As time passed, the gene was maintained for most mammals. This is because most mammals do not have Vitamin C in their diets. Primates, guinea pigs, and fruit bats get plenty of the stuff. They don’t need to make the protein, so they do not; it saves them in energy needed for its production. What’s interesting here is that as one looks at the sequence between different primates, it becomes more and more unrelated as one travels down the cousin road. The one nucleotide mutation is present in all primates, so it was inherited some time long, long ago. But other parts of the sequence differ in other ways. Human and chimp versions of GLO are more similar than human and orangutan versions because the former split more recently than the latter. Evolution is absolutely necessary if one wants to reason through any of this.

Filed under: Evidence, Evolution | Tagged: Jerry Coyne, Why Evolution is True | Leave a comment »