Ida is a new fossil discovery that has been horribly over-hyped. It is being called “the missing link”. Following sentences usually mention humans. In other words, some articles are crafty and don’t directly say this fossil is important to Homo sapiens. Others are less crafty. All of this non-sense plays right into the hands of the lying creationists (sorry to be redundant).

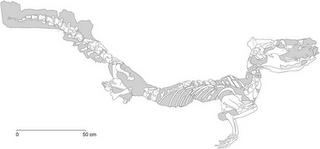

Darwinius masillae, otherwise known as Ida, is a tremendously well-preserved fossil that is a primate ancestor. As with most fossils, it was probably a relatively close cousin of one of our direct ancestors. (Note, “relatively close”. Of course, all fossils we find are eventually cousins of our ancestors, if they aren’t directly our ancestors.) How close is difficult to tell – forget saying it’s a direct ancestor. It is a member of the same suborder as humans (and apes and monkeys), haplorhine, but that doesn’t mean Ida wasn’t the last member of her particular population. It can tell us some interesting things, but it in no way independently confirms evolution. Science doesn’t work that way; theories are supported by a wide body of evidence. A single find can add a little weight to a theory, but doesn’t usually completely make a theory. (Notable, if this were found in the, say, Jurassic period, it would have been a find that actually spun evolution on its head – find me a part of creationism [or its coy, dishonest, lying cousin intelligent design] that can be falsified.)

So while interesting and not simply trivial, there are more important fossils out there than Ida. What’s more, there are more interesting fossils. (Guess which claim is the author’s opinion.) Here are some.

Filed under: Evidence, Evolution | Tagged: darwin, Darwinius masillae, Evolution, fossil, Ida, Lucy, Maia Cetus inuus, missing link, Schinderhannes bartelsi, tiktaalik | 1 Comment »